How M&A is Shaping the Banking Industry

Reduction of banks and how it affects our world today

By Alexandria Chun, Senior Online Editor

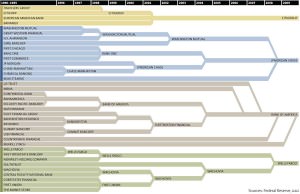

In 1995, there were many banks operating in the United States, thirty-seven of which were well-known firms. By 2009, only four of the thirty-seven remained. Where did all those banks go? How did such an extensive network condense into just four institutions? Through the power of mergers and acquisitions.

If you look at the major banks on Wall Street and Bay Street – Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, RBC, CIBC – a majority of them developed as a result of mergers and acquisitions. As their smaller predecessors clumped together, they integrated their pools of resources and products to form some of the most powerful financial institutions we see today.

So what is mergers and acquisitions, or M&A? As the name suggests, it’s the business of combining companies. Although the purpose of both these processes is to join two entities, they do have slightly different procedures.

An acquisition involves the purchase of most, if not all, of a target company. The acquirer owns all the old shares of its target. A merger, on the other hand, is when both companies surrender their stock, and issue a new one under the name of the new company. A true “merger of equals” is not common, however, since acquirers often seek to buy companies smaller than themselves.

If a company wants an existing product or service, they might find acquiring another company easier and more cost-effective than expanding its own. For example, it’s a lot faster and cheaper for you to go out and buy a light bulb than try to make one yourself (unless you already have all the tools and know-how to make light bulbs).

M&A deals are also made in different directions. Let’s say you own a lemonade stand. A horizontal merger could be made between you and another lemonade stand down the street. You could merge with a lemonade stand in a different neighborhood to extend your market reach, or you could merge with a vendor who makes iced tea to extend your product line. If you were to buy the lemon farm that supplies your lemons, you would be making a vertical merger, where a company acquires its supplier. Your lemonade business could also buy an unrelated business, such as a hat-maker. This is called a conglomeration.

Motives for deal-making range from practical to trivial. RBC improved its presence in Ontario and Manitoba by acquiring Traders Bank and Northern Grown Bank. BMO increased its service line by purchasing RBC’s credit and debit processing systems. To take advantage of a failing bank, JPMorgan Chase acquired Bear Stearns at a low price. These are all good, practical reasons.

Other motives include: an increased market share, synergy, increased buying power, hiring new talent, and reducing tax liabilities. Ultimately, all these motives are based on increasing shareholder value, and in turn, increasing revenue.

Occasionally, mergers are doomed by poor intentions. A company might hastily acquire other companies to create a monopoly, or a CEO might pursue unsound M&A deals simply because it will give them a nicer bonus. The resulting deals are often not well executed, and cost more resources than they procure.

Synergy is a very important concept in M&A. Apart from just being a cool word, it encompasses all the benefits of merging with another company. If done properly, a deal can increase cost efficiency by reducing overlapping staff or departments, increasing purchasing power, and acquiring new technology. Synergy is a goal of successful deal-making.

So if Company A wants to acquire Company B, they must first look at the pros and cons of the deal. Pros, as mentioned above, include diversification, geographical extension, larger market share, access to different technologies, reduction of financial risk, and the added incentive of a potential rise in value.

Cons can be found by valuation. Company A must evaluate how much they think Company B is worth. The deal can fail before it even starts if Company A doesn’t understand their target’s business and operations well enough. And if Company A approaches Company B with too low of an offer, it might create hostility. A deal can also fail after the merger with post-integration problems such as conflicting corporate culture, technological differences, and brand dilution.

It’s also a good idea to check the target’s books for misleading assets. Companies must avoid the mistake Bank of America made when they acquired Merrill Lynch. They had saved the failing firm only to find larger-than-expected losses on Merrill’s balance sheet. Executing thorough due diligence lets you know exactly what you’re buying.

Once the target is valued, the deal proceeds in stages. The first stage is buying the target’s stock. The acquirer can purchase up to 5 percent of the target’s stock before they must declare their intentions to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Now that the acquirer has a substantial stake in its target, they can make an initial offer called the tender offer.

Now the ball is in the target’s court. At this stage of the deal, they can do a few things, depending how they feel about the offer. If they approve, the deal can go forward. If they don’t approve, they can try to negotiate a better offer, issue new shares, or find another buyer. By issuing new shares to all existing shareholders (expect the acquirer) at a discount price, the target reduces, or dilutes, the acquirer’s position in their company.

Deals also have to be run past regulators to check if the new company will create a monopoly situation and diminish competition. These scenarios have a great impact on market diversity, and are particularly disadvantageous to consumers because competition leads to better consumer deals.

Regulation turned out to be especially important after the financial crisis of 2008. Deals throughout the 1990s and early 2000s gave rise to giant financial institutions that were deemed “too big to fail.” In 2008, banks like Bank of America and Citigroup had to be bailed out by the US government because their failure would have had widespread economic consequences.

Canada did not have these problems thanks partly to the government’s rejection of large bank mergers. In 1998, Bank of Montreal and TD were set to merge with RBC and CIBC, respectively. Paul Martin, the Finance Minister at the time, disallowed this because, among other reasons, it would have drastically reduced competition between Canadian banks and flexibility for customers.

Since 2008, M&A in the financial sector has declined substantially in volume and value because big deals aren’t happening like they used to. PwC reports that deal volume in the banking sector has decreased by 24 percent between 2010 and 2011. Many factors contribute to this decline, including stricter regulations, the European Sovereign debt crisis, and volatility in the markets.

So where does banking M&A look like it’s heading in the next few years? That depends on which banks you’re looking at.

Reports by both Merrill DataSite and Deloitte suggest that M&A activity is going to increase in small and mid-size institutions as they try to keep up with rising regulatory requirements. At their current size, smaller banks do not have enough capital to viably deal with increased operational costs and capital requirements. The reports also indicate that these increases, along with improved credit quality, will greatly encourage deal-making amongst smaller banks.

M&A activity between larger banks, on the other hand, is expected to decrease. Gordon Nixon, CEO of RBC, stated that because of strict requirements on reserve capital, the massive deals between banks that predate the financial crisis of 2008 are in the past. Big banks are now looking for ways to “fill in some of the holes that [the banks] have in some of [their] global platforms.” In fact, RBC is in the process of expanding its global wealth management business, which has been one of its ”holes.”

“That may sound less exciting than what you might have seen from 2000 to 2008, where you saw much bolder and more aggressive transactions,” said Mr. Nixon, “but clearly in today’s environment that’s not going to be something I think you’re going to see in the future.”

Indeed, others agree with Mr. Nixon’s outlook regarding the effect of regulations. Ivan Lehon and Omar Mizra at Ernest and Young Capital Advisors point out that the Dodd-Frank Act and Basel III are two regulations with the most influence on M&A activity in the United States.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, signed in 2010, aims to end “too big to fail” situations and protect taxpayers’ money from being used for bailouts. Basel III is part three of a global regulatory standard on banks set by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. This regulation includes capital requirements and regular stress tests to help prevent a financial crisis similar to the one in 2008. Lehon and Mizra believe that “[t]his has made banks think strategically about how they manage liquidity pools and which businesses are core versus non-core from a capital and liquidity perspective.”

Another key factor in the slowdown of banking M&A activity is the European Sovereign debt crisis. A PwC report found that European banks are beginning to divest non-core businesses in order to recapitalize and generate enough cash to help sustain themselves during the debt crisis. Although actual European M&A activity is unlikely to add to deal volumes, divestitures will create opportunities for acquisitions by other firms.

A third factor, volatility, is playing an interesting role in M&A activity. The volatility of the global markets is creating opportunities, even in such an unsteady time. A report by American Appraisal found that although high profile deals are being rejected to due uncertain economic conditions, these uncertain conditions may create other opportunities for smaller M&A deals. Large companies are beginning to divest their non-core businesses and streamline in response to market volatility, increasing the availability of high-quality targets at reasonable costs. That said, volatility is also preventing deals from closing due to lack of investor confidence. So it could have a dual effect on M&A activity.

Although this article focuses on the banking sector, M&A happens across all industries. It’s a major component of business that helps drive growth and increase efficiency. Although today’s global economic conditions are not suitable for the level of M&A activity seen in the past, new opportunities are still constantly emerging – and it’s up to deal-makers to find them.

Sources

– Financial Times “Harsh M&A landscape hits investment banks”

– Merrill DataSite “Financial Services M&A – the outlook for the banking sector”

– Merrill DataSite “Could the need to consolidate drive M&A in US banking sector?”

– Deloitte “Financial Services M&A in 2012: A cross-sector outlook”

– Globe and Mail “Blockbuster bank deals thing of the past, RBC head says”

– Globe and Mail “Economy Lab: Canadian banks now at door of exclusive club”

– M&A Alerts “M&A Banking Sector: Too Big to Fail in North America”

– Investopedia “Mergers and Acquisitions: Introduction”

– Investopedia “Biggest Merger and Acquisition Disasters”

– Mother Jones “How Banks Got Too Big to Fail”

– PwC “Balancing uncertainty and opportunity: 2012 US financial services M&A insights” March 2012 report

– PwC “Canadian M&A Retrospective and 2012 Outlook” January 2012 report

—————————————-

Liked this article? Hated it? Comment below and share your opinions with other ARB readers!

Share the post "How M&A is Shaping the Banking Industry"