Demurrage: A Miracle in the Town of Worgl

Demurrage: the DNA of tomorrow’s financial system?

By Jeff Fritz, Staff Writer

On July 5th, 1932, a miracle took hold in the small, Austrian town of Worgl.

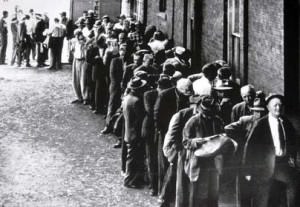

The Great Depression was in full swing and of its population of nearly 5000, a third were jobless, and at about 200 families were bankrupt. The situation was desperate. The town would try anything.

And in these extraordinary times, the town mayor, Michael Unterguggenberger (it’s actually fun to pronounce after the third try), decided on a radical intervention.

The town had 40,000 Austrian schillings left in its reserves. This was nowhere near enough to finance all the redevelopment projects Unterguggenberger planned. So instead, the mayor decided to invest this money into a special savings account as a guarantee to back a new type of money.

Back then, this new money was called ‘stamp scrip’. This is a ‘complementary currency’ that works by placing a kind of usage fee on money. In Worgl, the usage fee amounted to 1% per month of the money’s value, stamped directly onto the paper bills each month. This means that $100 at the beginning of the year would shrink to $88.64 by year’s end, compounded monthly.

As one can imagine, this usage fee turned the whole concept of saving and hoarding of money on its head. Why would you save your money when you know that the more you do, the more it loses its value?

But that’s the trick.

Instead of saving one’s money, stamp scrip creates the incentive to invest. And so did the residents of Worgl. With stamp scrip in place, they spent their money as fast as possible so they could spend it while its value lasted. They would spend on necessities, they would invest in their homes, lend to friends, some even paid their taxes early!

Meanwhile, the tax revenue, combined with the stamp scrip fee, the town collected was more than enough to help cover both the costs of the town’s redevelopment projects. In fact, the town generated enough money to build new houses, a ski jump and a bridge.

Meanwhile, the tax revenue, combined with the stamp scrip fee, the town collected was more than enough to help cover both the costs of the town’s redevelopment projects. In fact, the town generated enough money to build new houses, a ski jump and a bridge.

But the miracle lay in the fact that amid a global depression, Worgl reached full employment. Again, the key was stamp scrip. The speed that money changed hands (14 times higher than the national schilling) helped keep local businesses afloat and, in time, brought back the town’s lost jobs.

Things looked up for Worgl and Unterguggenberger. The town did so well that six neighbouring villages successfully copied the system and over 200 grew an interest in following suit.

That’s when the Austrian central bank panicked. They saw its monopoly rights on printing and gatekeeping money threatened. As a result, it outlawed Worgl’s stamp scrip system.

Soon after, Worgl saw its unemployment shoot back up to 30%, forcing its fell back into the country’s economic depression (the same happened to all other townships that copied Worgl’s system).

The brief history of money

The history money is a study unto itself. But generally speaking, money wasn’t so much an invention as it was evolution where form followed function.

As Sam Lanfranco, Professor Emeritus & Senior Scholar, Economics, York University, explained through an online interview, “Money was not invented in one place and then spread by knowledge migration. It evolved in many places in response to a troika of needs: for a unit of account, for a unit of exchange and for a durable store of value.

“Originally all monies were commodity monies, be that stones, shells, or various metals, so long as they were durable and relatively fixed in supply. Gradually, fiat (paper) monies evolved first as a convenience (as in the case of Italian goldsmith receipts) and then as a business, with the emergence of fractional reserve banking.

“Finally, in all cases, fiat monies in circulation have become a government monopoly.”

The concept of demurrage

When talking about money’s history, the topic of demurrage tends to come up. The modern omnibus term for stamp scrip (described above) and ‘negative interest’, demurrage refers to any system that places additional (per diem) cost to holding (or hording) money. One can argue other factors like inflation or interest share this same trait, but these have very different characteristics, as we will soon see.

The concept of demurrage has a long history, as long as the notion of rent. For centuries, different cultures used demurrage as a way to account for products with a limited shelf life or charge for holding items of worth. The Egyptians, for example, used this system when managing their stores of grain; the reason being that since grain eventually went bad, it made sense to charge a monthly fee to account for the spoilage. In Europe, demurrage was simply the fee charged for holding gold in the goldsmith’s vault.

These examples continue into the modern day, even if they’re no longer referred to as demurrage. Prof. Lanfranco noted how this concept is heavily used in the area of transportation: “(demurrage) commonly refers to the additional per diem cost of keeping possession of a transport unit (truck, railcar, vessel, etc.) that is tied up by loading or unloading delays beyond the time agreed upon. Railroads frequently keep each other’s rail cars for extended periods of time and settle up payments from a demurrage balance sheet.”

But as a theory, while notable greats like John Maynard Keynes and Irving Fisher supported demurrage as an ideal, economist Silvio Gesell has always been known as its greatest champion.

Velocity

Using Gresham’s law that “bad money drives out good,” Gesell argued that demurrage fees did the best job of speeding up a currency’s circulation (as seen in Worgl, where people couldn’t spend their money fast enough). Especially on the open market, when people know that keeping money is equal to losing money, then buyers and sellers will more actively engage with each other to meet in the middle and make deals and sales.

[pullquote]The more money you have, the more money you will lose on a recurring basis. Due to this new reality, a person’s natural inclination will change from wanting to own to wanting to give.[/pullquote]

As any ecomonist would say, when the velocity of exchanges and liquidity increases, so does overall economic activity. That is what Gesell believed was most prone to offer society.

In fact, such a system even has the potential to work wonders during economic downturns. Since during recessions, the natural inclination is to save and hoard money (thus worsening the recession), demurrage encourages the opposite—thus, cutting down the recession’s life span and improving economic resiliency.

Wealth diffusion

Another advantage that Gesell noted was that demurrage has the potential to discourage wealth accumulation.

Today, just owning money makes you more money (through interest). But with demurrage, wealth comes with a carrying cost. The more money you have, the more money you will lose on a recurring basis. Due to this new reality, a person’s natural inclination will change from wanting to own to wanting to give.

Under demurrage, if you have more money then you are able to spend, then it would make more sense to loan out that money (even at zero interest) to preserve that wealth, rather than keep the money and lose it gradually. As a result, wealth will shift from those who have the most to those who give the most and power will shift from those who have $1000 to those who have ten people owing $100 each.

The inflation killer?

Some would argue though that inflation does the same thing as demurrage, since inflation reduces the value of your dollar over a period of time. But more important, inflation is known to ruin economies (Zimbabwe anyone?), so if demurrage is similar, isn’t it bad as well?

The answer depends on perspective. Traditional currencies tend to get devalued by interest and inflation, as both work to create larger quantities of money, which oddly reduces its wealth (read the last issue’s feature article, All the world’s a cage, to learn more). Demurrage meanwhile is anti-inflationary. Since it works to reduce the money supply, it effectively increases the value of money (because less of it exists).

The death of short-term thinking

Our accounting systems promote clear cutting forests for immediate profit instead of logging sustainably forever, while our politicians promote robbing the future to pay for the tax breaks and subsidies of today. During an age of global warming, peak oil and demographic change, one of the greatest challenges facing mankind is its inability to plan beyond the next fiscal quarter or election cycle.

That is why the most important quality demurrage may offer is its encouragement of long term financial planning.

As noted above, demurrage punishes those individuals who keep their money instead of using or investing it. As a result, demurrage will train society to focus on how they can use their wealth to generate a comfortable living by investing in the long (instead of short) term.

As explained by Jordan B. MacLeod, author of New Currency: How Money Changes the World as We Know It, “Because of the … charge for idleness, money in the future will take on greater value than the present. This would reverse the current trend, where money in the future is discounted in favor of the present. This would make interest free loans attractive to the lender as a means of planning for retirement. It would also create an economic orientation favoring longer term planning and projects that integrate the concerns of society as a whole.

This storage fee, which originator Silvio Gesell called demurrage, would encourage everyone to spend what they need, and find other ways to ensure storage of wealth, such as capital investments, loans, etc.”

Too much of a good thing?

As much as there are supporters of demurrage, there are still many who have reservations about its effectiveness (no surprise here, considering demurrage is barely mentioned these days). Those who oppose demurrage rarely do so on ideological grounds, as many of the reasons argue for demurrage—like to address issues of inequity, poverty, social justice, etc—are widely supported.

The main reason demurrage isn’t supported is that it fails to meet, what Prof. Lanfranco calls, the “What, Why, How” test.

For one, supporters of demurrage usually tend to argue that money is the only commodity without a holding cost. Unfortunately, this ain’t the case.

As Prof. Lanfranco puts it, “There are three basic opportunity costs. The first is deferred consumption. The second is the interest foregone if balances are not loaned out. The third is that inflation deflates (money’s) worth as a store of value.”

[pullquote]This would imply that what are ethical challenges (what should we do?) are nothing more than technocratic challenges monetary demurrage.[/pullquote]

The second problem one has to consider is that in today’s advanced economic system, implementing demurrage may simply have no effect. In today’s markets, adding a demurrage-like charge on money may just be absorbed into the system as yet another “cost” of holding money, like interest or inflation.

“It is hard to understand,” Prof. Lanfranco added, “how one additional element in the cost of holding money would address the long list of socio-economic ills highlighted by proponents of monetary demurrage. A fixed demurrage fee would simply be an additional fixed factor for monetary policy to deal with, and there is clearly no scope for a second independent monetary authority with demurrage fee setting rights.

“There is virtually no evidence, nor a direct link, to suggest that using monetary demurrage to alter the opportunity cost of monetary balances would do anything other than complicate the application of monetary policy in the pursuit of broader policy objectives. Unlike transaction tax proposals, designed to reduce short-term speculative activity in currency markets, demurrage (if even practical) would have no more impact on financial system stability than do changes in central bank rates.”

Charles Eisenstein Interview for Money & Life Film from Charles Eisenstein on Vimeo.

Demurrage today

With the world recovering from its most dramatic economic seizure in decades, does the idea of demurrage even considered anymore?

A clue can be found in Sweden of all places. On July 8, 2009, Sweden breached the “zero barrier.” It cut one of its key interest rates (its deposit rate) to negative 0.25%

What does this actually mean? Basically, Swedish banks are paying 0.25% interest on all the deposits they’re holding in their reserves.

Does this sound familiar?

It should. Negative interest is modern day demurrage. It turns the concept of a bank account on its head, since instead of savers earning interest on their deposits, they are actually the bank to keep their accounts!

Why is Sweden doing this? Because they want to discourage people and banks from hoarding their money and encourage them to spend, invest and loan their money to benefit the economy.

The results of this strategy have yet to fully researched, but it proves demurrage is still alive and well.

No silver bullet

Best said by Prof. Lanfranco, demurrage shouldn’t be seen as a silver bullet for what are really difficult socio-economic problems. “(This would imply) that what are ethical challenges (what should we do?) are nothing more than technocratic challenges (monetary demurrage).”

This writer remains confident that demurrage may become a great tool the future uses to shape a fairer economic system. But it’s important to remember that ending issues like poverty, disease and global warming can only happen when humanity learns to work together through shared values and morals, and not through financial incentives.

ARB Team

Arbitrage Magazine

Business News with BITE.

Liked this post? Why not buy the ARB team a beer? Just click an ad or donate below (thank you!)

Share the post "Demurrage: A Miracle in the Town of Worgl"