Generation Y? More like Generation Dropout!

An in-depth look at today’s education trends in developed nations and an analysis of why Millennials are entering the labour market less educated than their predecessors

By: Michelle Monteiro, Staff Writer

It doesn’t matter that she isn’t a certified teacher yet, Salma Faress is a teacher nonetheless, it just happens to be at a Summer Camp.

Faress, 20, a fourth year student in the Psychology Stream of the Concurrent Education program at the University of Toronto, Mississauga campus, is one of the many in her generation, also known as Generation Y or the Millennial Generation (whatever floats your boat), who are joining the workforce less educated than those leaving it.

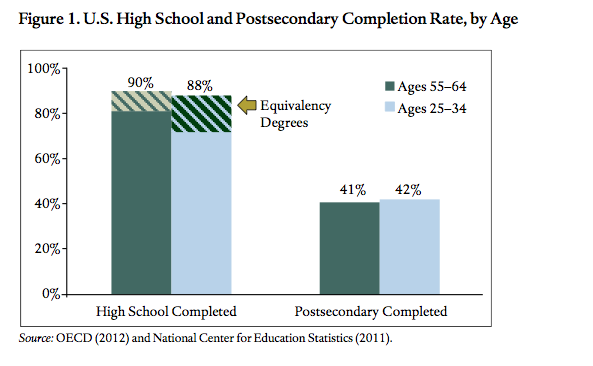

This phenomenon is unique in developed countries, especially in the United States, which is the only country listed in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a forum committed to seeking answers to common problems, that is below the OECD average.

The American education system has slipped over the past few decades, no longer being as internationally competitive as it used to be, according to a new June report from the Council on Foreign Relations’ Renewing America initiative. For fifty-five to sixty-four year olds, the United States has the highest percentage of high school graduates and the third largest of college graduates. But the percentage of people aged twenty-five to thirty-four in the country is tenth and thirteenth respectively.

“It’s ironic,” Faress noted upon coming across the trend. “There are so many privileges here that others anywhere else cannot even begin to imagine, and yet, those who do live here don’t take what’s offered to them.”

What about Canada?

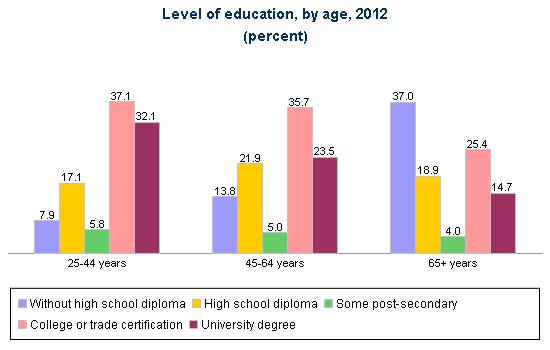

Canada has fared well in comparison to the United States. The percentage of individuals with high school diplomas aged forty-five to sixty-four is slightly higher than the Millennials. Other than that, the rates of post-secondary completion trail very close behind the rates of their successors. If countries were ranked on the share of people aged twenty-five to thirty-four years, Canada would jump from second to first, while the United States would drop from the highest rank.

Source: HRSDC calculations based on Statistics Canada. Table 282-0004 – Labour force survey estimates (LFS), by educational attainment, sex and age group, annual (persons unless otherwise noted), CANSIM (database).

The Great White North has the highest rate of college completion, consistently performing at the top level, topping competitor countries by more than ten percentage points. Since 1998, the country has increased its performance on university completion, edging closer to its higher-ranking peers, but it is unlikely that Canada will top the current leaders anytime soon.

For the most part, however, rates on secondary and post-secondary completion have been stagnant.

How do other developed countries compare?

According to the OECD Better Life Index on education, which scores OECD countries on educational attainment, student skills and years in education, Finland is the top-performing country in terms of its educational system with an index level of 9.5 out of 10. The percentage of Finns graduating from upper secondary education easily exceeds the seventy-five percent OECD average at more than ninety percent. Finnish students also tend to perform well regardless of their socio-economic background, which, unfortunately, cannot be said of the United States or even Canada. Japan is close behind in second place with an index of 9 and Sweden follows with a score of 8.2. Canada ranks tenth with 7.5. The United States’ score is a dismal 6.9, placing it nineteenth.

Out of the thirty-four countries in the OECD, Ireland has made the most progress, with a twenty-four percentage increase in its high school completion rate between 1997 and 2010. Over ninety-six percent of those aged twenty-five and thirty-four in Ireland have completed high school, while fifty percent of fifty-five to sixty-four year olds have.

| Educational Attainment (percentage of people aged 25-64, having at least a high school degree) | Student Skills (average performance of students aged 15, according to Programme for International Student Assessment) | Years in Education (average duration of formal education in which a 5 year old can expect to enrol during his/her lifetime until the age of 39) | Overall ranking in education |

| Czech Republic (92%) | Finland (543 score) | Finland (19.6 years) | Finland (9.5 index) |

| Japan (92%) | Korea (541) | Iceland (19.4) | Japan (9) |

| Russia (91%) | Japan (529) | Sweden (19.2) | Sweden (8.2) |

| Slovak Republic (91%) | Canada (527) | Denmark (18.8) | Korea (7.9) |

| Estonia (89%) | New Zealand (524) | Belgium (18.7) | Poland (7.8) |

| United States (89%) | Australia (519) | Japan (18.7) | Germany (7.6) |

| Poland (89%) | Netherlands (519) | Australia (18.5) | Australia (7.6) |

| Canada (88%) | Switzerland (517) | Greece (18.5) | Estonia (7.5) |

| Sweden (87%) | Estonia (514) | Slovenia (18.4) | Slovenia (7.5) |

| Switzerland (86%) | Germany (510) | Poland (18.2) | Canada (7.5) |

Source: http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/education/

Why does this trend exist?

So why are Millennials less educated than their predecessors when they enter work force? There are a few plausible explanations.

Too Many Compulsory High School Requirements: In Canada, these vary from province to province, but in the United States, mandatory subject requirements are common in nearly all American high schools. Essentially, in order for a student to graduate with a diploma, conditions must be met, certain courses must be taken. For Americans, this includes three years of Science, four years of Mathematics and English, at least one year of physical education. Simple enough, no? However, this provides a drawback for students. If we, as a society, are constantly viewing compulsory education as something “that we must do and get over with”, where is the incentive and desire to continue into post-secondary studies? We need to shift the mindset that education is an obligation and start seeing it as a privilege to be valued and respected. We also need to stop seeing schools as merely an institution where children are being supervised by teachers, parents should be regarded as the primary instructor in the educational success of their own children.

Post-secondary schools are expensive: For decades, tuition and fees have been outpacing family income and rising faster than inflation. It’s more expensive now than ever before to send a child to a post-secondary program of study. According to the Globe and Mail, Canada spends heavily on higher education over all — nearly $24000 per student compared with an OECD average of about $14200 — ranking Canada second among all OECD countries, behind only the United States. For numerous reasons, including expensive college maintenance, increased professor salaries and increased degree demand, students will continue to face an average tuition increase every year despite much financial aid, continuing to face an uphill battle, until the cost of higher education is addressed.

New Reality in the Job Market: Since the recession, the economy has shifted, and a growing number of people have lost their jobs. Needless to say, for the past few years, a solid, full-time position is something increasingly out of reach. The labour market now consists of a surge of part-time employment, all of which do not require a post-secondary degree to have. An Accenture survey found that forty-one percent of workers who graduated from college in the past two years say they are underemployed and working in a job that doesn’t require a degree. So if our reality is mainly part-times, jobs that will never need post-secondary studies, why bother pursuing it?

What can the past tell us?

The origins of these issues, surprisingly, and the answers we are looking for can be rooted forty years into the past. Let us use the United States as a case study.

During the first seventy years of the twentieth century, the high school graduation rate of American adolescents rose from six to eighty percent. One of the characteristics of educational policy became career-oriented education. The open education system approach had reached its height, involving learning that was initiated by the students themselves, dividing classrooms based on interest areas, and lessening mandatory courses and instead increasing the number of electives. By the sixties, the graduation rate ranked first among the OECD countries. As more and more graduated from high school, the increased proportion of the labour force that had a diploma became a driving force that fueled economic growth and rising incomes.

The seventies saw the rise of teacher activism, a broadening of the idea of civil rights in education. Nonetheless, the high school graduation rate flattened out around this time and stagnated for decades, while graduation rates in many other OECD countries increased markedly during this period. These countries, such as Finland, Germany and Japan, started incorporating a vocational education approach, an education that prepares students for specific careers, trades and crafts, providing procedural knowledge as opposed to theory. So what went wrong?

At this time, the United States developed a pattern of increasing high school graduation requirements. Requirements increased the nonmonetary cost of earning a diploma for students, especially for those entering high school with weak skills. In doing so however, they also lessened the value and effect of the financial payoff to a diploma, thus contributing to the stagnation in graduation rates over the last decades of the twentieth century and continuing into the twenty-first century.

So to summarize: education before the seventies was career-oriented, concentrating on the students’ interests for the future, rather than the general present-day requirements. Then beginning in the seventies, we began to see a shift in generalizing all students, who are all required to take at least the minimum amount of the same courses. Focus of the future in the long-term dissipates.

More Problems for Millennials?

The problem with these new graduation requirements was, and still continues to be, that they are too focused on getting a student into a post-secondary program, or any program, rather than guiding the student toward a career. Today, high school graduates and even college/university graduates are entering the “real world” with limited experience and a scarce amount of skills.

“Priorities have changed and our education has adapted to reflect those priorities,” commented Salma Faress. “Back then, when my parents were my age, life was focused on two things: career and family. You needed a career to provide food on your family’s table and that’s where education came into the picture. But now? A college or university degree is more about prestige than anything else. And prestige isn’t about perfecting, or even learning, skills.”

There are few job-prospect expectations for Millennials now. Not necessarily because they are less educated, but because they do not have the sufficient skills required to maintain the jobs available. As Baby Boomers continue to leave the workforce, employers are having a difficult time finding skilled young workers to replace them, producing long-term consequences on economic growth. Subsequently, the slow economy has shifted the way businesses hire: employers don’t need to build skills, they can simply hire them. And since Millennials are known for not having the right resources and skills for today’s labour market, companies are happy to retain the expertise of an older worker, rather than train a novice.

“It’s a vicious cycle worsening the problem,” Faress remarked. “One of my cousins is a lawyer but can only work at Holt Renfrew. How crazy is that?

I imagine it must be upsetting in a parent’s perspective, to immigrate to or live in a country with so much potential, but have their children live in a reality that has left them unprepared.”

Any solutions?

Perhaps the best suggestion is to expand education options that focus on life skills and work experience, as opposed to the traditional route of academic success. Graduation requirements should be loosened and businesses should collaborate with post-secondary schools to lead students toward pursuing careers. Salma Faress says there needs to be more application, rather than theory, a morphing of college and university into a single entity because right now “we’re only good on paper”.

Education has been the foundation for opportunity in countries such as Canada and the United States. But other countries have begun to outpace the best of the best. Times have changed and it’s time that schools change with them.

As the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, a group committing to ensure that all students in the United States have the opportunity to receive a high-quality education, puts it, “we live in a globally connected, information saturated world. To thrive, our students need to learn in and out of school, in person and online, together and independently. Students need learning experiences that meet them where they are, engage them deeply, let them progress at a pace that meets their individual needs, and helps them master the skills for today and tomorrow.”

Known as Michelle Monteiro, she’s been writing since her hands could grasp paper and pencils. She’s learned that a pencil is an extension of the hand and a gateway to the psyche. Currently, Michelle is an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, completing a BA in English. For more of her quirkiness, follow her blog at http://therealmichellemonteiro.wordpress.com.

Share the post "Generation Y? More like Generation Dropout!"