An Aging World = Social and Economic Timebomb

The Whole World is Graying

A Social and Economic Analysis of the World’s Major Economies: Japan, China and the United States

Alfred Yim, Staff Writer

Ryan Trinidad, Art Director

The issues of life and death are usually reported in the media only when something extraordinary or bizarre occurs. However, death and birth, far from being just interest stories, represent the continuous renewal and loss of life that subtly shapes the face of our society. As the collective human organism of a nation ages, the demographics of the country changes, potentially bringing about a new set of issues to contend with.

These changes will be examined in the three largest economies in the world: Japan, China and the United States. The potential effect of a little salt and pepper in their population mix will be discussed as it relates to each country’s international competitive advantage.

The Good Life Redux

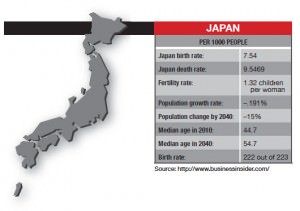

A blend of economic and social effects has set Japan on a course for population decline.Japan has been suffering ever since the burst of its economic bubble (from 1985 to 1990). The resultant downsizing and necessary cost cutting destroyed the warm notion of lifelong employment and company loyalty that used to exist.

With opportunities for employment diminished and with sustained employment a dashed dream, today young people who finally finish their long years of education are presented with a very bleak reality. Expectations people might have had about moving out of the ancestral home, owning a home of their own, finding a spouse and having a successful career are adjusted to accommodate the harshness of reality.

The stagnant environment has resulted in people giving up on achieving the three pillars of a ‘good’ life: education, a career and a family. Evidence of the first pillar being disregarded is the large number of youth who put little importance on excellent academic performance, which leads to non-participation in post-graduate studies.

The second pillar of a career is forsaken in favor of taking up non-stressful/dead-end part time jobs. Current estimates of the voluntarily under-employed number over 4 million.

Lastly, the third pillar of having a family is given up in light of the financial infeasibility of having one and the fact that workplace policies, in regards to prospective mothers, are discouraging. In short, depressed economic conditions have in part dissuaded couples from having children – the Japanese government is actually paying for people to have children.

Impact

What does population decline mean for Japan’s economy and competitiveness? Firstly we must ask what IS Japan’s special quality? The North American automaker would say that it’s their automobile industry. The Japanese ‘culture’ enthusiast might exclaim that it’s obviously the Tamagachis (yes, they are still being made) and animated cartoons. The automaker and the enthusiast are somewhat on target, but they miss the underlying cause.

Japan’s advantage in the international arena is due to its large population and domestic market as well as the high concentration of companies in its industries. The sizable domestic market allows companies to test their products before going international, thereby saving costs. It also lowers unit costs as companies can adhere to the ‘bigger is better’ mantra and have economies of scale. Finally, the high concentration in industries also encourages competition through research and development, which drives up innovation.

Japan’s advantage in the international arena is due to its large population and domestic market as well as the high concentration of companies in its industries. The sizable domestic market allows companies to test their products before going international, thereby saving costs. It also lowers unit costs as companies can adhere to the ‘bigger is better’ mantra and have economies of scale. Finally, the high concentration in industries also encourages competition through research and development, which drives up innovation.

Industries that have traditionally crutched on the domestic market, such as home electronics, will face hardship as the population dwindles. Though it is difficult to predict the implications for consumers, Japan’s place as an innovator in the realm of electronics could slip.

If a solution to Japan’s population decline isn’t found, it is expected that the labour force will drop one third from 67 million to 42 million by 2050. In turn, Japan’s large population, which is the source of the country’s competitive advantage, will be jeopardized.

Another problem of the demographic shift is that there will be more older individuals about than younger ones. This lopsided ratio would cause difficulties in funding medical insurance and pension systems.

So what’s the bright side of population decline? Japan has the smallest per capita land mass of all G-7 nations and it is bestowed with very few natural resources. Therefore, a population decline in light of these two facts would prove beneficial with fewer people fighting over the same resources and assets. Energy consumption, for instance, would decline.

[pullquote]Simply put, the unprepared will find themselves making the grim choice between their healthcare needs and food/utilities.[/pullquote]

The reduced demand due to a population decline would also lower costs of such resources and would even lead to lower property prices, which would be particularly welcome in places like Tokyo. Also, with the birth and death rates as they are, there will be fewer younger people, meaning there would be less spending needed on schools, public buildings and infrastructure. This could all mean lower taxes.

However, the current-day situation is not looking so good. Japan’s GDP per capita has decreased in conjunction with the shrinkage of the working age population. Paul Krugman cites that Japanese GDP per capita fell from 88% of US GDP per capita to 76%. Working-age adults as a percentage of population have decreased from 69.7% to 64% from 1992 to 2007.

China began in its single child policy in 1979, as a result of the government’s desire to curb problems related to overpopulation. Because of this policy, China’s population is estimated to be about 400 million less than what it would have been otherwise.

That single child policy may come back to bite China’s politicians. Single children are now faced with the prospect of supporting two parents and up to four grandparents. As soon as 2020, the working age population will peak, and in 2050 the over-60 population of China will be larger than the entire population of America.

Deeper than Cheap

China’s competitive advantage has always been its ample supply of relatively cheap labour, which has fueled its explosive economic growth. However, that advantage is fleeting because of two reasons. First, China’s working-age population is quickly approaching its peak. Second, the government is implementing policy to rebalance the economy through increasing wages and the consumption factor of its GDP.

With recent events like the Foxconn suicides (at Apple Inc.’s Chinese manufacturing plant) undergoing media scrutiny, wages as well as working conditions are being given a necessary facelift. Governments and companies are also under more pressure from Chinese workers (particularly the exploited migratory workers) who are taking part in very large and frequent protests (upwards of 300,000 protests in 2005 alone).

With recent events like the Foxconn suicides (at Apple Inc.’s Chinese manufacturing plant) undergoing media scrutiny, wages as well as working conditions are being given a necessary facelift. Governments and companies are also under more pressure from Chinese workers (particularly the exploited migratory workers) who are taking part in very large and frequent protests (upwards of 300,000 protests in 2005 alone).

Places like Guangdong, for instance, have seen pay increases of 24 to 32% since a massive Honda strike was held.

In short, China cannot sustain its competitive advantage of cheap labour for much longer. Furthermore, this does not even consider the population decline that will begin in 2035, resulting in massive changes to the labour market.

Despite the negative connotation of rising wages to businesses, Lee Li, associate professor of marketing at York University, argues that China will continue to maintain a competitive advantage. Simply speaking, “It’s not just about cost,” and that China’s advantage is deeper than most people think. The notion that Chinese firms are content with worker exploitation as their bread and butter strategy is a gross simplification.

Why is it that low-cost locations like Vietnam and Bangladesh have not achieved a similar industrial cost advantage as China?

Professor Li says the separating factor is that China has a combination of skillful labour, infrastructure, communication systems and banking systems. Therefore, larger and more sophisticated companies (e.g. technology companies) that rely on these systems and need skilled workers will likely continue their operations in China. Smaller companies and those in less sophisticated industries such as textiles will find it easier and more cost-effective to move away.

China’s other advantage over countries like Bangladesh is in “cluster-related” factors. Cluster-related samples, Li says, are simply the surrounding businesses and members of a geographical cluster which accrue benefits to a business. For example, a nearby adhesive-making factory would be very beneficial to a business that uses the adhesive to create end products.

[pullquote]… China cannot sustain its competitive advantage of cheap labour for much longer.[/pullquote]

On the issue of pensions, China’s health insurance coverage for all but the affluent is particularly worrying. We as Canadians take for granted the fallback that the government provides us when we are ill.

In China, millions of retired persons have only their single offspring as their source of post-retirement income. In the rural areas where over 60% of China’s population resides, more than half of the elderly do not enjoy medical insurance and only 4.8% receive pensions.

The phenomenon of aging in America requires a mention of the post-war “baby boom”. After WWII, males coming back from the war started families in earnest. In particular, the United States had approximately 79 million babies born between 1946-1964. Now, because of this wave of post-war births, the number of grizzled people (age 65 and over) will double over the next 30 years, from 40 million to 80 million. The percentage of older people in the population will increase from 13% to 20%. In fact, by 2011, all 79 million baby boomers will be over 65 years of age.

A Booming Headache

The three major effects of aging in the United States would be the issue of paying the 79 million or so baby boomers their pensions, the effect of the older population on the savings rate (and subsequently the economy) and the strain on the government because of healthcare issues of the elderly.

For instance, a study has found that America’s 100 largest corporate pension plans were underfunded by $217 billion at the end of 2008. This is a huge problem when about half of US workers have less than $2000 saved up for retirement. Simply put, the unprepared will find themselves making the grim choice between their healthcare needs and food/utilities.

For instance, a study has found that America’s 100 largest corporate pension plans were underfunded by $217 billion at the end of 2008. This is a huge problem when about half of US workers have less than $2000 saved up for retirement. Simply put, the unprepared will find themselves making the grim choice between their healthcare needs and food/utilities.

Social security is also in a fragile state. With 35% of Americans over 65 relying on social security as nearly 100% of their income, and the fact that the system pays out more benefits than it receives in taxes, the political and social landscape is set to explode.

How to deal with social security is certainly a headache for politicians. For instance, if the government just decides to print the money they need to deal with the shortfall of cash inflows, it would likely be too politically dangerous to consider as a viable solution.

Also, with US unemployment still high and around 46% of Americans disapproving of the Democrats’ efforts, Alena Kimakova, Associate Professor of Economics and Public Policy at York University, comments that the US pension system has problems both on the public and private side.

“Private pension funds suffer from risks associated with market downturns, employers going out of business or reneging on their pension contribution obligations,” says Kimakova. “Even in unionized environments, employers’ liabilities towards pension funds often get less consideration in negotiations than maintaining employment levels or avoiding shutdowns and moving operations overseas.”

Therefore, Professor Kimakova states, entitlements for younger contributors to the system will likely drop and/or change, which would be the most viable political alternative as it allows for the “time-distancing” of the unpopular measure. Things just seem more acceptable if the pain is deferred. She goes on to say that a gradual increase in the full retirement age has already been implemented.

[pullquote]… as the world quietly grows older, these trends will become apparent pretty quickly as they will have a lasting impact on every corner of the globe.[/pullquote]

“Those who were born in 1960 or later face a full retirement age of 67, compared to those born between 1943 and 1945 having 66 years as the normal retirement age, for example.”

Furthermore, Kimakova suggests that the US social security system could stand to be more progressive, because as of now, even the well-off are entitled to payouts due to the fact that the system only uses age as a benchmark.

On the issue of the savings rate and its effect, Kimakova says, “Traditionally speaking, American households have had very low savings rates and this is in part due to the developed financial markets in the US, which gives better access to loans for individuals, who then use these loans for consumption purposes.”

There are economic benefits to accessible loans, one of which includes the countering of wealth inequality and boosting economic activity and the GDP. However, the low interest rate environment (due to high productivity, well-developed financial markets, stable institutional environment, etc.) might be changing in light of the large public deficit and prolonged downturn of the economy.

Consequently, the effect of economic growth in the short to medium term is likely to be negative because domestic consumer spending has been the main driver of the US economy. However, the long term effect will be a beneficial one, as people will be saving more and living within their means.

As for the healthcare strain due to aging, the federal government will certainly feel the impact as Medicare pays for 56% of the elderly’s healthcare bills. In fact, public coverage of the elderly (Medicaid and Medicare) is 60% of healthcare spending for the 65+, while private insurance accounts are only 14%.

A silver lining, if any, would be the fact that the elderly spend upwards of four times the amount on healthcare as those under 65. This involuntary preference of the elderly to “consume” health services would likely facilitate a boom in the health industry—and there is evidence of companies already positioning themselves for the windfall.

Conclusion

In the case of Japan and US, they stand to lose their competitive advantages of a large domestic market and consumption respectively due to population aging. In the case of Japan, its strong cultural stance has resulted in an extremely closed immigration policy. This simply piles onto the negative growth, as its own citizens, for many reasons such as pessimistic economic expectations, either do not want to have children or cannot.

In regards to the US, low interest rates due to various advantages such as having the reserve currency of the world set as US dollars, have made it easy to take on more loans and thus marginale the idea of saving.

With lending at an all-time low and the fact that people over 65 tend to spend less, economic growth, as said before by Professor Kimakova, is definitely going to suffer in the next ten years. Meanwhile, China’s competitive advantage will likely remain due to infrastructure and institutions, but its main problem of pensions will likely become a major issue.

Despite these major issues and trends, it is surprising how demographic changes are rarely ever noticed. However, as the world quietly grows older, these trends will become apparent pretty quickly as they will have a lasting impact on every corner of the globe.

ARB Team

Arbitrage Magazine

Business News with BITE

Liked this post? Why not buy the ARB team a beer? Just click an ad or

Share the post "An Aging World = Social and Economic Timebomb"